Það hafa sagt við mig menn að í landslagsmálverki sé heldur lítil frásögn. Í besta falli megi greina af gömlum slíkum myndum hvort jöklulbungur hafi verið háreistari um aldamótin nítjánhunduð en þær eru í dag. Og á slíkri greiningu sé jafnframt og ævinlega fyrirvari sem snýr að sannferðugleika þess sem pensilinn hefur mundað hverju sinni.

Ég er sammála því upp að vissu marki að klassísk landslagsmynd eigi að vera sannferðug – í þeim skilningi að í myndinni megi greina stund, stað og tíma. Stundin er hvenær dagsins, tíminn er hvenær ársins og staðurinn er … ja þar á landi sem þér finnst þú vera niður kominn. Sú forsenda gefur vissulega til kynna að staður geti afstæður og jafnvel eingöngu til í hugskotinu. Ég hef minnst á þetta í fyrri póstum um sagnir af landi og frásögnina í verkinu. Tengist því að sjálfsögðu að stundum er heiti myndar nauðsynleg tilvísun til sagnar eða þess staðar sem lagt er út frá.

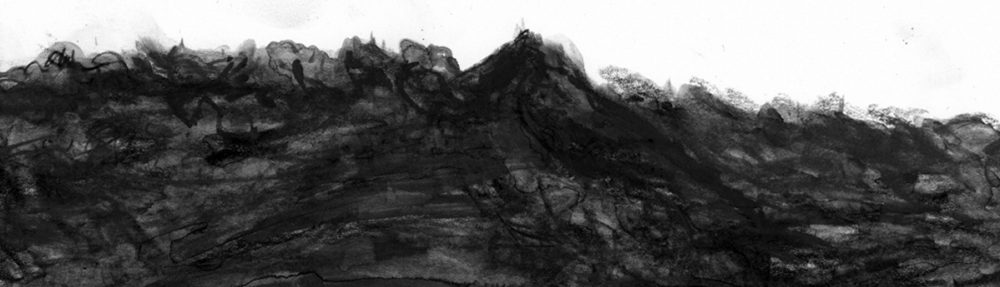

Með þetta hugfast er ég þeirrar skoðunar að teiknuð eða máluð mynd af landi geti sagt töluverða sögu. Og ég fer ekki ofan af því að sú saga geti meðal annars verið um landsins lund og líðan. Er til dæmis alveg handviss um að birkihlíð sem er undirlögð af „feta“ einhverrar tegundar hefur það tiltölulega skítt. Og þar segir liturinn eiginlega alla þá sögu sem segja þarf.

birkihlíð akvarella 20×29 2018 // birch-slope aquarelle 20×29 2018

// I am sometimes told that there is very little narrative in landscape paintings. At best such pictures can be used to derive how a given glacier was shaped at turn of an earlier century. And it always follows that such use hinges on the truthfulness of whoever it was that was responsible for operating the brush.

I concur that a ‘classic’ landscape picture should be truthful – in the sense that it should be possible to gather a notion of circumstances in terms of when and where, including the season and time of day.

As to the locality the references become – for me – a bit fuzzy. As to where; this is wherever it seems to you to be the place. This premiss indicates of course that the locality may be an abstraction and perhaps only existing in the mindset. I have mentioned this in earlier posts on legendary lands and the narrative in the work. Obvious furthermore that sometimes the name given to a picture is a necessary reference to a story or given place.

Bearing this in mind I think that a narrative may be included when drawing or painting land. And I firmly believe that the story may reflect how the land is ‘inclined’ (and not in the geological sense). Likely for example that a birch-slope festered by moths is not having the best of days. And the colour really says it all.

Interesting reflections. Yes I think season and time of day/weather important in a landscape. More so than exact place, especially in the wide open spaces of Iceland.

Nice to see your recent work.

Thora